|

26.12.3 NEEC 赤字はFredによる修正 感性と文化(コメント) 今回は、2014年9月5日付New York Times紙 の「Can’t place that smell? You must be Americanーその匂いがわからないの?貴方、アメリカ人でしょ」と言うタイトルの記事がTextでした。女性エッセイストが書いた長文で難解な記事でしたが、一言で言えば、 味覚などの感覚は歴史や文化により育てられるもので、匂いや味の表現も文化が違えば異なると言う趣旨の内容でした。私は、日本人と西欧人の美意識の違いについてコメントしました。

|

|

|

本日の記事のキーセンテンスは、”sensory perception is culturally specific(感性は文化により異なる)”である。味覚などの感覚は文化により育てられるもので、同一のものに対しても文化が違えば感じ方が異なることが世界中の20以上のグループを対象とした実験で確認されたと言う内容で大変面白い。本日のテーマに関して私は、日本人と欧米人の感性の違いについて述べて見たい。但し、私のコメントは、記事にある五感の違いに関するものではなく、美意識を含む情緒に関するものである。

1.もののあわれ/ほろびやすさ まず、日本の文化における「もののあわれ」と「ほろびやすさ」について述べて見たい。我が国の「(形あるものの)非永続性」と言う感覚は、もののあわれと言う情緒に発展した。中世の日本文学の多くに共通なのは、情緒とは、悠久の自然の中にあって、人間のはかなさと物事の移ろいやすさの中に美を見出す感覚であると見事に喝破されていることである。誰もが滅び行くものを見るのは悲しい。欧米人然りである。しかし日本人は、滅び自体に美を見出すのである。日本文学者ドナルド・キーンは、これこそが日本人が他民族と違うところだと言った。 |

The key sentence in this article will be “sensory perception is culturally specific.” It is very interesting that sensory perception is raised by culture and it was confirmed by the experiment against over 20 cultural groups around the world. Today, I would like to comment on the difference of sensitivity between Japanese and Western people. However, my comment is not about the five senses, but about the emotion including a sense of beauty/an aesthetic sense.

1.MONO NO AWARE/HOROBIYASUSA Firstly, I will explain “mono no aware” or the fragility in Japanese culture. The sense of impermanence evolved into the emotion that we call “mono no aware”, or the sense of the pathos of things. Running through much of the Japanese literature of the Middle Ages, this emotion is best defined as the sensibility that finds beauty in the fragility of mankind and in things changeable amidst the permanence of nature. Everybody grieves at the sight of things in decay. Western people do, too. But the Japanese sense the beauty that is inherent in that fragility. Donald Keene, the Japanese literature scholar, sees this as a sensibility that is unique to the Japanese. |

|

・もののあわれについては、お茶の水大の数学者・エッセイスト藤原正彦教授が著した『国家の品格』の中に次のような一節がある。

―スタンフォード大学の教授が私の家に遊びに来た。秋の夜食事をしていると、網戸の向こうから虫の音が聞こえてきた。その時この教授は「あのノイズは何だ」と言った。教授にとって虫の音はノイズ、つまり雑音だったのである。その言葉を聞きながら、私は信州の田舎に住んでいた祖母が秋になって虫の声が聞こえ、落ち葉が舞い散り始めると、「ああ、もう秋だねえ」と言って、目に涙を浮かべていたのを思い出した。「なんでこんな奴らに戦争で負けたんだろう」と思ったものである― 日本人は、秋の虫の音を聞くと手を休めてあたかも音楽でも聞くかの如くその方向へ頭を巡らす。日本人の耳には自然が奏でる音は雑音などではなく音楽と響くのである。 |

The

Dignity of a State (Kokka no Hinkaku in Japanese) is a book by the famous

Japanese essayist and mathematician Masahiko Fujiwara. The book criticizes

the emphasis on Western logic in Japanese society and calls for a return to

what is described as ancient Japanese virtues. Fujiwara introduced ―About ten years ago, a professor from Stanford University came round to my house for a social visit. It was fall, so as we had our dinner, we could hear the sound from outside. “What’s that noise?” my guest inquired. For a Stanford professor, the sound of the insects was only so much noise. I remember thinking to myself: “How on earth did we lose the war to characters like this?” ― When Japanese hear the autumn insects, they stop what they are doing, and turn their head, as if listening to a distant music. For Japanese ears, nature sounds are never noise, but music. |

|

・ほろびやすさについては、次のような例がある。 西洋の建物が主として石で作られるのに対し、日本の伝統的建築は、決して永久的ではない木材で造られる。我が国は、やがて朽ちてしまう建物を新陳代謝しながら、つねに新しくし永遠に生きながらせようとしてきた。 伊勢神宮の式年遷宮は全社殿が20年毎に建て替えられる。神宮とは、天皇家の先祖天照大御神を祀る内宮と、食べ物・穀物を司る神を祀る外宮の二つの正殿を中心とする125の神道神社の総称である。正殿を含む神宮の全社殿が造り替えられる。言うなれば、神は20年毎に新しい神社で快適に過ごされることになる。遷宮は正殿を現在の正殿の隣に位置する区画に移す儀式で、ここに新しい正殿が建てられる。新しい神社は1千年以上も前に建てられたと同じ姿に生まれ変わる。こうしたやり方で文化が引き継がれる例は世界のどこにもないであろう。 太古の昔より日本人は、木が朽ちゆくことをあらかじめ見越して家を建てるのである。

|

As for “horobiyasusa”( the things in decay,) there is the following example: While Western building is made mainly with incorruptible/tough stone, the traditional Japanese architecture is built with corruptible/fragile wood. Japan has renewed the architecture so as to perpetuate forever, always replacing the old with the new. The

“Shikinen sengu (Reconstruction)” of the Ise Shrine is the most typical

ceremony From ancient times, Japanese built the architecture in anticipation of decay of wood. |

|

2.自然との共生か自然の征服か 日本人特有の感性の一つに自然への処し方がある。日本人の感じ方や生き方の特徴は、その住居の形に見事に表れている。日本の伝統的な家のつくりは、外界に面した廊下/濡れ縁があり、雨戸が大きく開いて外と家の内とがつながるようになっている。縁側は、生活に溶け込んできた日本特有のものであり、庭先から縁側に腰を下ろすと、身体の半分を室内に、残り半分を外界に置くと言う姿勢になる。そこには自然を生活の中で味わい、生活の中に取り込もうとする意志が存在する。一方、西洋の建築は、はっきりと壁によって外界と家の内部は仕切られ、わずかに窓が開いていて、外光と空気を入れる仕組みになっている。家の内部は完全に外の自然から隔離され、人の出入りは戸口のみであり、自然から離れて自分を守る形になっている。この住宅建築に見られる違いは、日本人と西欧人との間に、人間と自然とのかかわりについて根本的な差異があることを物語っている。即ち、西欧人は自然を対立するものと見、自然を支配しようとしてきたのに対し、日本人は自然との共生をはかろうとしてきた。

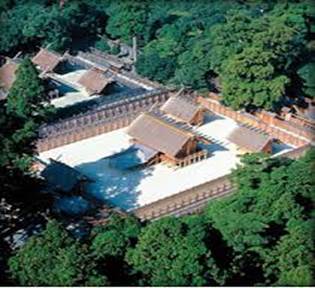

日本建築の特徴を代表する例として桂離宮がある。京都郊外にある江戸時代の17世紀に皇族八条宮の別邸として創建されたこの建物と庭は日本建築を代表する作品であり、しばしば“日本美の極致”と評される。これを最初に世界に紹介したのは、昭和初期、ドイツから日本へ亡命した世界的建築家ブルーノ・タウトであった。桂離宮は欧米の建築界を驚嘆させた。 タウトはこれを「泣きたくなるほど美しい」と大絶賛し、一切の装飾を排した簡潔の美は西欧近代建築の美と共通する新しさも備えていると評した。 タウトは離宮の穂垣を見て、傍にしゃがみこんで泣いたと言う。日本人はそれほど巧みに自然と人工物を渾然一体とすることに長けているのである。

|

2.Symbiosis with nature vs. Conquest of nature One

of the sensibilities peculiar to Japanese is an attitude toward nature. The

Japanese love of nature is well expressed in the architecture of their home.

The traditional Japanese home has the passage faced outside named “nureen (an

open veranda)” and “the shoji (paper sliding door)” opened widely On the other hand, in the Western architecture, a house is clearly divided by the wall into internal and external world, and small windows serve merely to take daylight and air. The inside of house is completely isolated from nature and going in and out is limited only to the entrance door. The Western architecture has a style to protect dwellers, diverging from nature. The architecture tells us that there is a distinct difference between Japanese and Western people over the ways in which people involved themselves in nature. That is to say, while Western people have regarded nature as an opposing object and tried to govern it, Japanese have coexisted with nature. For an example of the Japanese architecture, the Katsura Imperial Villa (Katsura Rikyū in Japanese) is a villa with associated gardens and outbuildings in the western suburbs of Kyoto. Katsura Rikyū is a pivotal work of Japanese Architecture, often described as the "quintessence of Japanese taste.” First revealed to the world by Bruno Taut, the great architect, who defected from Germany in the early Showa period, Katsura stunned the architectural community of the West. Bruno Taut mentioned about Katsura Rikyu, “It makes me almost cry, it is so beautiful, the simple beauty of the building without having any decorations was estimated to have the same value as the beauty seen in modern architectural modeling.” As a matter of fact, when he saw the hedging system of Katsura Rikyu, he sat down beside it and wept. The Japanese really are remarkable when it comes to blurring the boundaries of the natural and the manmade. |

|

3.結論 一言で言えば、日本の文化とは日本人の感性そのものであると言えよう。アメリカのイリノイ州立大学のボーナー教授は、感性と言う意味を持った言葉は日本特有のものであり、感性の文化を世界に向けて発信してほしいと期待を寄せている。 |

3.As a conclusion, in a word, it can be said that Japanese culture is the Japanese sensitivity itself. A professor, Illinois State University says, “I hope Japan disseminates the culture of sensitivity to the world since the word with the meaning “sensitivity” is particular to only Japan.”

|

|

|

|