|

29.2.8 NEEC

“子ども食堂”の出現(コメント) ―増え続ける我が国の子供の貧困―

戦後、東洋の奇跡とまで言われた経済成長を成し遂げたお陰で、我が国では貧困問題はとっくに解決されたものと広く信じられていました。ところが最近になって本問題が再燃、貧困世帯の子どもに食事や学校用具などを提供する運動が各地で広がって来ているそうです。 今回のテーマは、今年(2017年)1月17日付 英ガーディアン紙が取り上げた埼玉県川口市の「子ども食堂」とその背景にある子どもの貧困に関するもので、「Japan's rising child poverty exposes true cost of two decades of economic decline(増え続けている日本の子どもの貧困は、失われた20年の経済不況で本当に犠牲になったのは誰かを示すもの)」 と言う記事です。 前回、「妄想彼女」のテーマでは、人口の減少が我が国最大の問題であり、その背景に若者が結婚しない・セックスしない風潮があること、人口の再生産が我が国喫緊の課題であることなどをコメントしましたが、今回のテーマは、子どもに義務教育すら満足に受けさせられない貧困家庭が増えているという、今後、国民の質の低下を危惧させる問題です。

|

||

|

1.埼玉県川口市の子ども食堂について今年1月17日付けの英ガーディアン紙は次のように伝えている。 川口市―東京北部の人口50万強の都市―の子ども食堂は、世界で最も豊かな国の一つである日本で、公式に350万人―17歳以下の6人に1人―いると見積もられている貧困の子ども達に食事を与えるために作られた数百の子ども食堂のうちの一つである。 過去4年間で全国に300以上の子ども食堂が出来、その半数強が過去12ヶ月の間に出来たものだという。2013年(平成25年)時点でそれは21店だった。因みに、OECDは貧困家庭を国民の平均家計所得の半分以下の家庭と定義している。 2016年3月にこの食堂を創設した佐藤匡史氏は、“今ここで夕食をとっている50人そこらの子供達のほとんどがみじめな貧乏暮らしをしているわけではないが、彼等のうち何人かはちゃんとした食事がとれない家庭から来ている。 ここで食事をとっている子ども達の3分の1が片親である。また、家が貧しいことに屈辱(スティグマ)を感じるが故に、多くの親たちは自分達が貧困家庭であるとは決して言わないし、また、利用をためらう親子もいる”と言う。 川口子ども食堂は、地元企業からの寄付金や農家が提供する食材と子ども達の家庭が供出するもので成り立っている。全国の子ども食堂のほぼ半数は無料で、残る半数の店も親達にはやや高めにしているものの子ども達には100円から300円で食事を提供している。

|

British daily newspaper “The Guardian” as of Jan 17, 2017 reported on the children’s cafeteria in Kawaguchi, Saitama prefecture, Japan as follows: ―Children’s cafeteria in Kawaguchi, a city of just over 500,000 north of the capital, is one of hundreds to have sprouted up in Japan in recent years to provide meals for some of the estimated 3.5 million children – or one in six of those aged up to 17 –officially living in poverty in one of world’s richest countries. More than 300 children’s cafeterias have opened around Japan in the past four years, more than half of them in the past 12 months. In 2013, there were just 21. Incidentally, the household classed as experiencing relative poverty is defined by the OECD as those with incomes at or below half the median national disposable income. Mr. Masashi Sato who opened the cafeteria in March 2016 says, few of the 50 or so children eating dinner in the cafeteria are living in abject poverty. Several, though, come from families who cannot afford to feed them properly, the children who eat here every month, about a third come from single-parent families. A lot of families would never describe themselves that way because of the stigma they attach to poverty, or some families to make use of the cafeteria. The Kawaguchi cafeteria survives on cash donations from local businesses and food provided by farmers and some of the families themselves. About half of the cafeterias feed children for free, while others typically charge between 100 yen and 300 yen, with parents paying slightly more than their children.―

|

|

|

|

Volunteers prepare meals at a children’s cafeteria in Kawaguchi, Saitama prefecture, Japan(ガーディアン紙が撮影した川口市子ども食堂のボランティアによる食事づくり)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

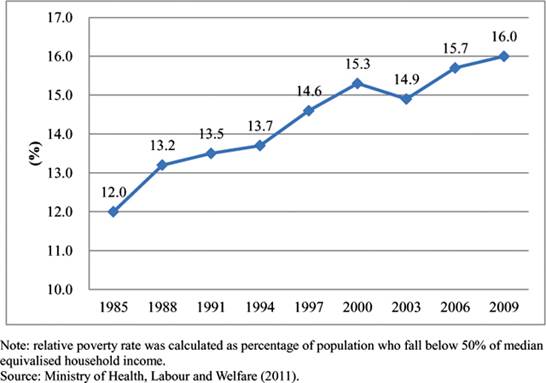

2.貧困問題の再燃 我が国の貧困に関し、国立社会保障・人口問題研究所は2014年の報告書で次のように述べている。 ―最近まで我が国では、貧困問題は既に解決されたものと広く信じられていた。我が国が経済成長を成し遂げ、平等な社会を作り上げたという思いは、日本人の誇りとアイデンティティの源となって国民の意識深くに染み込んでいる。 事実、既に1960年代頃には、人々の生活水準は急速に向上し、第二次世界大戦後の食糧難問題は過去のものとなっていた。“中産階級国家”という言葉は、1970年代の日本を言い表すために考え出された用語で、全ての国民がー最も恵まれない人々でさえ経済成長の利益を享受して来たと信じられていた。 政府は、1960年代には貧困に関する統計の収集や出版物の発行を止め、政治家の演説からも貧困の語は消えた。しかし、1970年代以降ずっと日本の貧困率は着実に上昇していた。下図で明らかなように、日本の相対的な貧困率は、1985年から2009年の間に4%増大している。この数値は、OECD加盟国の中で貧困率上位5カ国の一つに数えられる高い数字である。更に子ども達の貧困については、厚生労働省の最新の調査によると、子ども達の何と16.3%が、2012年現在の国民平均所得の半分以下の所得の家庭で生活しているーこれは2009年から0.6%、2003年から13.7%増加していることを示すものである。この数値は、冒頭述べたように日本では概ね6人に1人の子どもが貧困であることを意味し、2010年のOECD加盟国の平均値13.3%を大きく上回っている。また、政府が1985年に調査を始めて以来、子どもの相対的貧困率は国民の平均貧困率16.1%を初めて上回った。 2000年代後半になると政府もついに貧困問題があることを認めた。2009年には、厚生労働省は相対的貧困率を発表し、2013年(平成25年)6月19日には子どもの貧困対策法が成立、翌年1月から施行された(下記<参考>参照)。

|

On the re-emergence of poverty in Japan, the year 2014’s report issued by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research indicates as follows: Until recently, it was widely believed that Japan had solved the poverty problem. The notion that Japan had achieved economic growth and achieved an egalitarian society has sunk deep into the Japanese public consciousness so much so that it has become a source of national pride and identity. In fact, already back in the 1960s, the living standard of people was rising rapidly and problems of food shortage after World War II had become things of the past. The term “a middle-class nation” was coined to describe Japan in the 1970s and it was believed that all people, even the most disadvantaged, had benefited from the economic growth. The government stopped collecting and publishing statistics on poverty in the 1960s, and poverty dropped from the policy discourse. However, since the 1970s, Japan’s poverty rate has been rising steadily. As the figure below indicates, the relative poverty rate of Japan has increased 4 percentage points from 1985 to 2009, making Japan one of the top five countries among the OECD countries with a high poverty rate. As to the child poverty, according to the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry’s latest survey, a record 16.3 percent of children lived in households that earn less than half the national median income as of 2012 — 0.6 percentage point higher than in 2009 and up from 13.7 percent as of 2003. The figure, which translates into roughly one in six children in Japan, topped the 2010 average of 13.3 percent among OECD member countries. The relative child poverty rate topped the national average of 16.1 percent (covering adults as well) for the first time since the government started taking relevant surveys in 1985. The government has finally recognized the problem of poverty in the late 2000’s. In 2009, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced the relative poverty rate and in 2014, the Law on Measures to Counter Child Poverty was enacted. Relative Poverty Rate of Japan

|

|

|

前述の子ども食堂創立者佐藤氏は、子どもの貧困の原因について次のように言う。 増え続けている子供の貧困は、“失われた20年間”の経済不況による真の犠牲者が誰だったかを示すものである。2008年のリーマンショックによって引き起こされたグローバルな経済混乱は、我が国の20代・30代の女性を直撃した。正規雇用で働いていた彼女たちは、低賃金でボーナスも定期昇給もない非正規の仕事やパートタイムの仕事に追いやられた。時に彼女たちは金を借りる必要に迫られ、時々サラ金から金を借りるようになり、その返済のために所謂風俗業に身を落とす羽目になった。彼女たちがこうした負のサイクルに陥いるのはいともたやすいことだった。

|

Mr. Sato, the cafeteria’s founder says Japan's rising child poverty exposes true cost of two decades of economic decline. The global economic turmoil sparked by the Lehman shock in 2008 hit women in their 20s and 30s particularly hard. “Those in full-time work were forced to take irregular or part-time jobs with low pay and no bonuses or annual pay rises. In some cases, these women have to borrow money, sometimes from loan sharks, and then end up working in the commercial sex industry to pay off their debts. It’s easy for them to get trapped in a negative cycle.”

|

|

|

政府は、子どもの貧困の増加は、1990年代以降のデフレ傾向の下で世帯所得が長期間低迷したままだったことによるとしている。子どもの貧困はまた、片親家庭―その多くが母子家庭―が増加していることを反映している。そうした家庭の母親の約半数は、子供の面倒を見る必要があることから、低賃金のパートタイムや非正規の仕事に就くことを余儀なくされている。こうした片親家庭の子どもの貧困率は54.6パーセントにまで跳ね上がっている。 専門家は、子ども貧困問題は、本質的に、両親が揃っている場合でも子育て年齢期の若年世代の間に貧困が増え続けていることによると言う。本問題の背後にある根源的要因は、我が国の労働者全体に占める非正規雇用の割合が高くなっていることにある。90年代以降、パートタイムのような非正規雇用の労働者が急激に増加し、2013年時点で1900万人、国の労働者全体の約4割(37%)を占めるまでになっている。これは企業が人件費を抑制するために正規雇用の従業員を減らし、低賃金ですむ非正規従業員を雇用するようになったためである。 |

The government attributes the rise in child poverty to the long-term decline in household income under the deflationary trend since the 1990s. It also highlights the increase in the number of single-parent families — mostly single-mother households. Roughly half of the mothers in such households are hired in low-paying part-time and other irregular jobs because they need to take care of their children. The child poverty rate among these single-parent households shoots up to 54.6 percent. Some experts say the problem of child poverty essentially reflects the increasing poverty among the younger-generation households in child-rearing age, including families that have both parents. A decisive factor behind this problem is the growing ranks of the nation’s workers hired in irregular jobs. Since the 1990s, the number of people with irregular jobs such as those with part-time contracts has increased rapidly to hit 19 million in 2013, or about 37 percent of the nation’s employed workforce, as businesses cut back on full-time employees and relied more on low-paying irregular workforce to trim manpower expenses.

|

|

|

4.国の抜本的な対策が必要 政府の調査によれば、高等教育を受けることの出来る子どもの割合は親の収入に比例し、(彼等の就職後の)平均生涯所得は教育レベルに比例するという。貧困ライン以下の家庭の子ども達は、特別な補助がない限り、高等教育を受けることが難しく、就職後も低賃金の仕事に就くことをやむなくされている。 政府は、高齢者層には特に厚く子育て家庭には薄い現行の硬直した社会福祉の予算配分を見直し、将来世代のための投資を実質的に増やすべきであろう。子ども食堂が全国あちこちに出現し始めたのは、政治家達が真剣に向き合わなければならないより根深い問題があることを示す。 2014年1月に施行された子どもの貧困対策法は、専門家が言うには、救済を必要とする子ども対策には十分な予算が手当てされないばかりか、官僚組織の非効率性と政治の無作為によって少しも進展が見られないと言う。子どもの貧困・教育支援団体日本協会代表理事の青砥恭(あおとやすし)氏は、「安倍総理は子どもの貧困、いや一般的な貧困についても関心を持っているとは思えない。理由は簡単で、貧困問題は票にならないからである。政治家達は、選挙期間中だけこの問題に触れるが、子ども達が今どう言う状況にあるのか、今から40年50年後に彼等がどんな人間になるのかなどに思いをいたすことは全く出来ていない」と言う。

|

Official statistics and surveys show that the ratio of children receiving higher education goes up in proportion to the income levels of their parents, so does their own average lifetime income. Children of families living below the poverty line often find it difficult to go on to higher education and are more likely to end up taking up low-paying jobs — unless they receive extra support. The government should review the rigid allocation of social welfare budget, which is heavily spent on support for its elderly population but little on families with children, to substantially increase its investments for the future generations The popularity of children’s cafeterias reflects a wider problem that Japanese policy makers are struggling to address. Although the Law on Measures to Counter Child Poverty was enacted in January 2014, experts say programs to help needy children are underfunded and held back by bureaucratic inefficiency and political apathy. “I do not believe that Abe has any interest in child poverty, or poverty in general … for the simple reason that it’s not a vote winner,” Yasushi Aoto, chairman of the Japan Association of Child Poverty and Education Support Organizations. said. “Politicians only seem to think about the short-term. They’re unable to think about the lives of children today and the people they will become in 40 or 50 years from now.”

|

|

|

<参考> ●子どもの貧困対策法とは? 子どもの貧困対策法、正式名称「子どもの貧困対策の推進に関する法律」は、平成25年(2013年)の第183回国会に議員立法の法律案として提案され、衆・参両院の全ての政党の賛成のもとに平成25年6月19日に成立した(施行は26年1月から)。 ●子どもの貧困対策法の目的は? 子どもの貧困対策法の目的は、法律の第一章総則に以下のように記載されている。 (目的)第一条 この法律は、子どもの将来がその生まれ育った環境によって左右されることのないよう、貧困の状況にある子どもが健やかに育成される環境を整備するとともに、教育の機会均等を図るため、子どもの貧困対策に関し、基本理念を定め、国等の責務を明らかにし、及び子どもの貧困対策の基本となる事項を定めることにより、子どもの貧困対策を総合的に推進することを目的とする。 ●子どもの貧困対策法の内容は? 子どもの貧困対策法は、第一章から第三章と附則の四部から構成されている。 第一章総則(第一条―第七条) 第二章基本的施策(第八条―第十四条) 第三章子どもの貧困対策会議(第十五条・第十六条) ・第一章総則では、子どもの貧困対策法の「目的」「基本理念」「国の責務」「地方公共団体の責務」「国民の責務」「法制上の措置等」「子どもの貧困の状況及び子どもの貧困対策の実施の状況の公表」について定められている。 ・第二章基本的施策第八条で、 政府は子どもの貧困対策を総合的に推進するため、子どもの貧困対策に関する大綱を定めなければならない。大綱には次に掲げる事項について定めるものとするとしている。 ・第三章子どもの貧困対策会議第15条で、 内閣府に、特別の機関として、内閣総理大臣を長とする子どもの貧困対策会議を置くとしている。会議は、次に掲げる事務をつかさどる。 ●子どもの貧困対策法「大綱」はできたけれど、その後はどうなるの? 子どもの貧困対策法「大綱」が閣議決定されたが、今後どのように子どもの貧困対策は進められるのか? 子どもの貧困対策法の第四条に以下のようにある。 第四条(地方公共団体の責務) 地方公共団体(都道府県及び市区町村)は、法律と大綱に基づき、国と協力のうえ、地域の状況に応じた施策を策定・実施する義務を負う。 また、子どもの貧困対策法の第九条に以下のようにある。 第九条(都道府県子どもの貧困対策計画) 地方公共団体のうち都道府県は、「大綱」に定められた基本方針を勘案して、子どもの貧困対策についての計画を定めるように努めるとされている。しかし「努める」という言葉が示す通り、子どもの貧困対策計画の策定は義務ではなく努力目標とされている。 このように、今後、都道府県においては、子どもの貧困対策計画が策定され、都道府県・市区町村等すべての地方公共団体では、地域の状況に即した施策が策定・実施されることとなる。 |

|

|