|

25.12.11 NEEC 赤字はFredによる修正 春画−(コメント21)

最近ある日の新聞広告欄で、“死ぬまでに見ておきたい日本の文化と言われるのが春画である”と言う謳い文句を見つけました。これで思い出したのが、もう5年も前になるのですが、英語教室でテーマになった大英帝国博物館が日本の「春画展」を開催したと言うニュース(Kyodo October 2013 Major exhibition of Japanese erotic art opens in London)です。当時のイギリスのメディアによれば、3ヶ月にわたって展示された170点の春画は、行儀のよいイギリス人を吐きそうになるくらい熱狂させ、格式高い展示で有名な同博物館をついには官能の見世物館に変えたそうです。ここのところ私の投稿は少子高齢化問題に関連した“固い”話題が多かったのですが、今回はその時の春画展に関する“やわらかい”コメントを投稿します。ご覧頂ければ幸甚です。

|

|

|

春画とは、特に江戸時代に流行した性風俗を描いた画のことを言う日本語である。ほとんどの春画は通常木版画の形で作成される浮世絵の一種である。春画は文字通り春の画と言う意味だが、“春”と言う文字は、“性交”を示す婉曲的表現であることで知られている。本日は、春画がどのようにして国内外に広まったのか、また、春画の特徴は何かについて述べて見たい。

1.江戸時代、春画が国内で流行した理由は、現代の若者がポルノ雑誌や写真を求める理由と同じであろう。春画の出現は、17世紀に始まった日本と都市化と符合する。特に江戸への人口集中が際立っていた。そして江戸の人口の3分の2が男性であり、しかも井原西鶴が名付けたように“独身達の都市”であった。折しも道徳規範の厳しい折柄、こうした若者が遊べるような安価な岡場所は少なかった。その欲求を満たしたのが春画であった。春画は安価であり、汚しても構わず捨てることも出来た。また、春画には災難よけの一種のお守りとしての機能があった。武士は鎧の下に男女性交の図を厄除けの守りとして忍ばせ「勝絵」と呼ばれ、後世になると商人が火事を避ける願いを込めて蔵に春画を置いたという。また、特に枕絵の絵巻は花嫁の性教育のテキストとして女性の間でも使われた。

|

“Shunga”

is Today, I would like to comment on how shunga spread domestically and internationally, and what characteristic the picture has.

Probably,

one reason why shunga became popular in the Edo era The

appearance of shunga coincides with the urbanization of Japan, beginning in

the 17th century. The cities were demographically unbalanced, none more so

than Edo. Two-thirds of Edo were male, prompting the novelist Ihara Saikaku

to call it a “city of bachelors.” At the same time this city was severely

disciplined and not many could afford what pleasure quarters there were.

Shunga thus filled a need. They were cheap, stainable and disposable.

Moreover, it was considered a lucky charm against death for a samurai to

carry shunga, and a protection against fire in merchant warehouses and the

home. Also, despite claims of educational use (pillow books for ignorant

brides), shunga

|

|

2.西洋に初めて春画が伝わった時期は明らかではないが、イギリスに初めて春画がもたらされたのは、1614年に日本から帰航した東インド会社所有のクローブ号(日本に初めて来たイギリスの商船)と言われている。日本で得た文物はオークションで売りさばかれたが、宗教の影響力が強かった欧州では、春画は猥褻であるとして破棄された。 物語性とユーモアを交えた春画は、葛飾北斎や北川歌麿などの芸術的な浮世絵師によっても描かれた。春画を優れた絵画として高く評価したのは、ジャポニズム時代のフランスの美術家たちである。また、大英博物館が初めてコレクションの一部に春画を加えたのは1865年のことだ。 以後、春画は洗練された芸術のひとつとして、欧米の芸術家から高い評価を得てきた。 一方、我が国では、最近はやや緩和されたものの、1世紀前は、外国人に笑われるとして春画を没収した経緯がある(今話題の“特定秘密”を守るためではなかった)。 外国人が笑っているのは、欧米から輸入した芸術作品の局部すら日本では今なおボカシを入れていることだそうだ。

|

Although

it is not clear when the first shunga got across to the West, it is generally

said that “the Clove,” a ship possessed by the British East India Company,

which voyaged to Japan for the first time, brought it back to Britain in

1614. While cultural products obtained in Japan were sold off at the auction

in Europe, shunga collections were Meanwhile, though there have recently been some reproductions in Japan allowed, a century ago, law enforcers in Japan were confiscating erotic art because “it might cause the foreigners to laugh at us.” (It was not to ensure protection of the current controversy “specially designated state secrets.) Now, more liberated countries are truly laughing at the spectacle of a Japan continuing to blot its imported obscene pictures and still hampering public showings of some of the finest works in its artistic heritage.

|

|

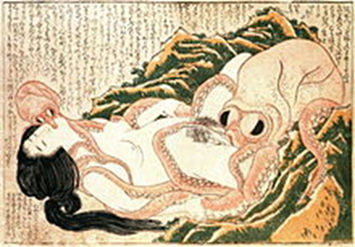

3.英国における展示の反響 イギリスのメディアによれば、今回の春画の展示は熱狂的レベルに達していると言う。行儀のよいイギリス人が春画を見て吐きそうになっているらしい。格式高い展示で有名な大英帝国博物館が、ついには官能の見世物館に変わっていると言う。世界で最も悪名の高いジャンルの一つでありながら、素晴らしく面白く、学術的に破天荒で、奇妙に印象的である。実際この展示は、喜びと楽しみを醸し出しており、春画が笑い絵と別称される意味がよくわかると評判のようだ。しかし、不気味な展示物もある。あるコーナーには、悪名高いあの蛸を含む化け物やこの世には存在しない生き物との性交絵が展示されている。海外で最も知られている春画は、「蛸と海女の性交」図であると言われるが、この絵は何とあの「神奈川沖浪裏」を描いた世界で最も有名な浮世絵師・葛飾北斎の手になるものなのである。こうした高名な浮世絵師たちが春画を描いていることに、初めて春画を見る観客達は驚いているらしい。

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, Hokusai, 1814

|

The exhibition of shunga had major repercussions in London. According to the recent British media, it seems that this display has reached fever-pitch in the press. Britain’s usually well-behaved gallery-goers are, quite frankly, gagging for it. A museum famous for its “blockbuster” exhibitions has finally served up a “bonkbuster” — this is a superbly interesting, academically groundbreaking, and oddly touching display of one of the world’s most infamous artistic genres. Indeed, this show exudes delight and amusement — it was with good reason that one early alternative term for shunga was warai-e, or “laughing pictures.” But there are dark corners, too. One case holds a creepy selection depicting sex with monsters and supernatural creatures, which contains “the notorious octopus.” Yes, that’s the octopus — probably the most famous work of shunga known outside Japan, depicting a pearl-diving girl in coitus with cephalopods. It is the handiwork of Katsushika Hokusai, who can equally lay claim to creating the most famous Japanese artwork known outside Japan — his woodblock print “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” (1829-32). This may be the most surprising insight the visitor with little prior knowledge of shunga takes away with them — that many of these erotic prints came from the hands of the Japanese artists most celebrated today.

|

|

4.春画の特徴 +その描写は必ずしも写実的でなく、性器がデフォルメされ大きく描かれることが多い。 外国人専門家は、日本人にはそうする理由があると言う。西洋絵画では性器の描写は抑制されている。欧米人の場合、思春期になると生まれつきエロティックな体付きになり、所謂「二次性徴」が顕著である。しかし日本人の体付きはこの二次性徴が目立たない。それが逆に性器を際立出せて描くことになった理由ではないかと言う。 (女児の場合、二次性徴とは、恥骨、腋窩、下肢の毛髪の成長のほか、乳房の隆起、腰の幅の増大などである)

|

Shunga couples are often shown in nonrealistic positions with exaggerated genitalia. According to a Western analyst, a frank depiction of genitalia had reasons for the Japanese people. The Western genre of the nude downplays the genitals. With so much erotic power inherent in the secondary sexual characteristics (*), it can afford to. But the people in Japanese prints have few secondary sexual characteristics (though their clothing may have some) and there is “not much else of a bodily kind for shunga to show.” This is perhaps one of the reasons for the magnification of male genitalia. * Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty, especially those that distinguish the two sexes of a species, but that are not directly part of the reproductive system. Secondary sexual characteristics include growth of pubic, armpit, and leg hair; breast enlargement; and increased hip width in girls.

|

|

+性交場面で男女とも着衣している 春画に登場する男女はほとんどが着衣したままである。江戸期の日本では、男女ともお互いの裸は混浴の公衆浴場などで見慣れており、裸体にエロチシズムを感じなかった。逆に、着衣は芸術的な狙いと共に、男女の生業を推察させ、且つ、身体の他の部分を覆うことで局部の描写を際立たせる効果があった。

|

In almost all shunga the characters are fully clothed. This is primarily because nudity was not inherently erotic in Tokugawa Japan – people were used to seeing the opposite sex naked in communal baths. It also served an artistic purpose; it helped the reader identify courtesans and foreigners, the prints often contained symbolic meaning, and it drew attention to the parts of the body that were revealed, i.e., the genitalia.

|

|

+説明書きが極めてリアリスティックで可笑しみがある 春画は性交をあからさまに図に描くだけでなく、直截的な文章が書かれている。しばしば男女の対話の形で書かれ何とも可笑しみがある。例えば・・(あとは英文でご理解下さい)

|

Shunga not only shows uncut images, but also includes the texts that explain integral parts of the image. Often in the form of dialogues, these texts are usually lightly humorous. For example, the dialogue that accompanies an image of a husband being fed sake by his wife emphasizes how, flaccid, he is plainly between bouts: Husband: Tonight it feels particularly good, perhaps because of the moon-viewing. Wife: Me too. I’ve climaxed five times tonight. Husband: Let’s take a break and have a bit of sake. Wife: You’ll only poison your body. Husband: You’re more poisonous than any sake.

|

|

|

|